Forgotten

One of my favorite web-sites is Forgotten New York, where obscure or hidden pieces of old infrastructure are placed into the context of

It is harder to do in

Just west of the Rose Quarter Max stop on

These rails are something much older.

They lead back to a time when three cities;

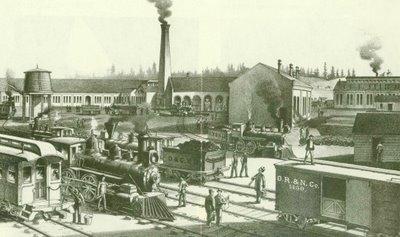

The Oregon Railway & Navigation Company's shops at Albina in the 1880s. The chimney still exists today, next to Union Pacific's Albina diesel facility.

The arrival of the Oregon Railway & Navigation Company (controlled by the transcontinental Northern Pacific Railroad) in 1883 was a watershed time in

With a connection to the rest of the country’s rail system,

At the time,

Ben Holladay, the "Stagecoach King".

In 1873, construction of his Oregon & California Railroad got bogged down in the mountains south of Roseburg, forcing him to sell his interests to Henry Villard, who would eventually connect Portland to the east with the Oregon Railway & Navigation Company.

The Oregon Railway and Navigation Company built through Sullivan’s Gulch and established yards, shops and a company town at Albina. Despite Ben Holladay’s fondest wishes, a passenger terminal was planned on the west side of the river, and necessarily, a bridge across the

In granting a franchise across the river, the City of

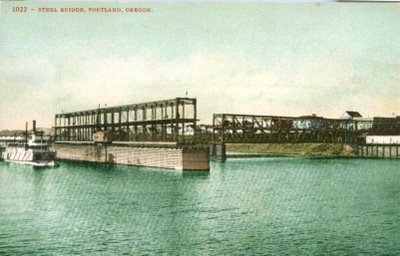

Construction began in July 1887. The bridge opened for rail traffic a year later on July 11, 1888. It soon became known as the “

Construction began in July 1887. The bridge opened for rail traffic a year later on July 11, 1888. It soon became known as the “A year and a half later, construction began nearby on Grand Central Station, now known as Union Station.

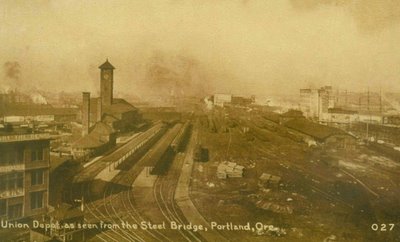

"Union Depot" taken from above the upper deck of the Steel Bridge, near Hoyt Street, circa 1911.

The upper deck the

Ironically, at

The east end of the old Steel Bridge. The ridges in the pavement were caused by the collapse of the rotted streetcar track's ties. Old cobblestones are to the right.

Third, at

The bridge then crossed

Portland’s first electric street railway line, operated by the Willamette Bridge Railway, entered service Friday November 1st 1889, on the Steel Bridge.

The route began at Third and

Two years later, the Smithson Block, which now houses the Widmer Gasthouse pub, was built at the intersection.

The initial mile and a half long line gave birth to what, through expansions and corporate consolidations would become the great pre-World War I Portland Rail Light & Power system.

“In a few minutes the words, “All right, go ahead,” was spoken, when the young man manipulating the lever, turned on the subtle fluid, and away the car sped. It ran rapidly and with scarcely any jar. There was none of that jerky motion so common to the horse, steam or cable car. “How very smooth she runs,” every body exclaimed when the car got fairly under way and went spinning across the big bridge.”

- The Oregonian, Saturday November 2, 1889, describing the electric-powered streetcar trip.

Car #20 of the

“A carriage containing Mr. and Mrs. William Sheehy of

When Ben Holladay was not building railroads, buying legislators or entertaining the ladies, he was buying land, a lot of it, in

His Holladay Addition ran west from

The

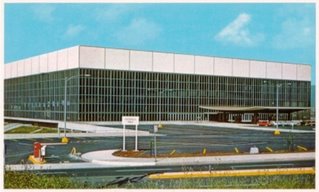

Years later, in the early 1950’s, Portlanders would decide they needed a sports complex, an idea which would evolve into Memorial Coliseum.

In a conflict that Ben Holladay would certainly have understood, there was a dispute over which side of the river the complex would be built on.

In 1956 the issue was decided by the voters in a referendum that favored of the east side by a margin of 303 votes.

Memorial Coliseum’s eventual location between the Broadway and

It bordered the vital jazz club scene along William’s Avenue, described vividly in “Jumptown, the Golden Years of Portland Jazz” by Robert Dietsche, with nightspots such as the Dude Ranch, (where Lois Armstrong would play), the Savoy, the Frat Hall and Lil Sandy’s.

The demolition of the area was the first of three hammer blows to Portland’s African-American neighborhoods (followed by the placement of Interstate 5 through North Portland and destruction of much of old Albina in the re-development that accompanied the building of Emmanuel Hospital).

It is widely rumored that “those-in-the-know” bought up property in the neighborhood before it was known to be the future site of the Coliseum, then sold the land at great profit to the city.

The area around Holladay Street in the 1940s. The red dot indicates the location where the rails and cobblestones are showing through the pavement today. The line of paved over tracks can be traced to where the old Steel Bridge met East Portland. The grain elevator is still in place, with additional silos.

Of the neighborhood very little remains. Like the original

Gone.

Almost.

The Gerding’s Lyrical Precedent...

A few years ago when I first heard about the Brewery Blocks redevelopment, I began to worry about the old

I was relieved when the building was saved. A fun evening spent watching “West Side Story” finally allowed me to see it from the inside. Portland Center Stage has done a wonderful job. With its gorgeous interior, environmental innovation and historic setting, the Bob and Diana Gerding Theater at the Armory is a fine example of preservation and re-use.

Strangely enough, it is not the first theater in

Below is the Lyric Theater at 133 Seventh (Broadway after 1913) on the corner of Seventh and

5 comments:

You mentioned the Pantages as being "...on the corner of Seventh and Alder Street (the present location of the Bank of California Building)..." but isn't the bank actually between Washington and Stark?

I think the building (one block south) with the "Flowers by Dorcas" shop is the one between Alder and Washington. In fact, I went in that shop and the man who runs the place has a couple old photos of the theatre, he pointed out an old original theatre staircase, and I think he has one of the old theatre's chandeliers above his cash register area.

There's a photo of the building I'm referring to up at http://www.flickr.com/photos/41894180030@N01/369638555/

And I understand there was another Pantages (it had been the Empress before), that then later became the Orpheum (where Nordstroms is today).

Dan, I've been in love with your blog for awhile now.

I was riding down Interstate today and noticed a re-paving project happening near the site of the old Steel Bridge tracks. I stopped to make sure they weren't tearing up the tracks (they're not--yet), and it occurred to me that that would be a great site for a small Streetcar Park. Unearth the tracks and cobblestones, remove the small parking area right there (which rarely seems to get used), and put some plaques up detailing the intriguing history of the area, and of Portland's rail history in general.

Relatively cheap, easy to sell to Commissioners/Metro... What do you think?

Regarding the Ancient Order of Workmen's Temple. I've often wondered what it looked like originally. Obviously the cornice (sheet metal?) is missing, but some windows are blocked up as well. I've always hoped someone would restore it. With those small, cross-barred windows, though, it presents the same problems that the Masonic Temple at 39th and Hawthorne has: windows that seek to keep prying eyes out.

Bravo. What a lovely site. Reminds me of The Music I heard in Portland 30 years ago. When jazz was no-cover and raucous in both northwest and northeast Portland. When there were still great dive gin-joints near the waterfront. When one could hop off the train at Union Station and find a hotel downtown for $5 a night or $10 without the cockroaches. I am researching a magazine story about the Ben Holladay addition and the brothers, Charles X. Larrabee and S.E. Larabie, who bought it in 1887, and stumbled across your site. Love the photos of the tracks peeking through the asphalt and the cobblestones under the asphalt veneer. Great stuff. I will visit again.

Noel V. Bourasaw

www.skagitriverjournal.com

skagitriverjournal@gmail.com

While I loathe the so-called "pearl district" as much as (or most than) most locals, I must admit that I am thrilled with what they've done with the Armory.

Whle I've not ever been inside the building, it is really the last piece of land around here that brings the Brewery to my mind (strong memories of peeking in the large doors and seeing pallets of Mickey's stacked high...), plus it is just a beautiful old building and piece of history.

Post a Comment